The Road Hunter

by Steven T. Callan

1-6-2017

Website

“That’s strange,” said Berg, pulling to a stop and reaching for his binoculars. “What’s that fancy new car doing out here in the middle of all these rice fields?” It was mid-morning in early August 1954, and the enthusiastic young rookie warden was patrolling for pheasant poachers near the Northern California farming community of Biggs.

Born in 1925, Berg had enlisted in the U.S. Marines at seventeen and become a World War II veteran by the ripe old age of twenty-one. After completing high school and working for several years at various state jobs, five-foot-nine-inch, 175-pound Gilbert Joseph Berg began what was to be his life’s work as a warden for the California Department of Fish and Game.

I asked Berg, now eighty-nine, about the men he worked with in those days.

“Well,” said Berg, “Don Davison was the captain in 1954. Gene Mercer was in Chico, Jim Hiller was in Willows, Will Payne was in Oroville, and Lloyd Booth was in Orland. Old Lloyd was a few years from retirement and used to sleep through all the squad meetings and training sessions. We all thought that was pretty funny. Dave Nelson didn’t become captain until just before your dad took over the Orland position in 1960. I had so much fun in those days, I was disappointed when my days off rolled around.”

“Tell me about your district,” I said, eager to know what being a warden in the northern Sacramento Valley was like during the early 1950s.

“The Feather River and lower Butte Creek ran through my district, so there was plenty of salmon poaching activity during the fall spawning season,” said Berg. “During the winter months, you might see a million ducks rise up in the evenings and head out to the rice fields. Most of the commercial duck poachers were down in the Butte Sink and around Gray Lodge Wildlife Area. We worked damn long hours but loved every minute of it. And pheasants … boy, did we have pheasants! The road hunters out of Chico, Oroville, and Gridley kept us busy all year ’round.”

Speaking of road hunters, Berg segued to the Willie Ray Slack case he had made sixty years before. The Slacks were a large family of outlaws and ne’er-do-wells out of Chico. They didn’t believe in laws, particularly game laws, and had been thorns in the sides of area Fish and Game wardens for many years.

Bill Slack, known to his friends and family members as Willie Ray, was forty years old, six feet tall, and heavy around the middle. An obnoxious braggart, he liked driving fancy cars and was seldom seen without a stogie in his mouth. Willie Ray was a building contractor, specializing in barns, sheds, and horse corrals. Everyone who worked for him was a cousin or shirttail relative. The area Fish and Game wardens used to say, “When the Slacks aren’t pounding nails, they’re usually out killing something.”

On that memorable day in early August 1954, Willie Ray Slack was driving his pride and joy, a brand-new baby blue Plymouth Belvedere, through the rice fields of western Butte County. Berg had received reports of closed-season pheasant poaching in the area and was staked out at the west end of the field behind a pump shed, a patch of tall weeds, and a rusted-out tractor with three flat tires. Sitting in the driver’s seat of his 1952 Ford sedan patrol car, he watched as the out-of-place automobile, a trail of dust billowing behind it, meandered eastward toward Biggs.

The mid-morning temperature was well on its way to ninety degrees, and the humidity among thousands of acres of flooded rice fields was stifling. Sweat poured from Warden Berg’s forehead into his eyes as he tried to focus his binoculars on the Plymouth sedan. Each time he saw the suspicious car’s brake lights come on, Berg would climb from his patrol car and position himself to see what the driver was doing.

“I stayed about a half mile away so he wouldn’t spot me,” said Berg. “The car would stop, and seconds later I’d see a rifle barrel pop out the driver’s-side window. The driver would walk out and pick something up, fool around at the back of his car, and close the trunk. I found it puzzling that I could hear the trunk slam shut but never heard a gunshot. When the suspect sped up and began to drive away, I decided it was time to make a stop.”

Jumping back into his patrol car, Warden Berg raced after the speeding Plymouth. Approaching from behind, he reached up with his left hand and switched on the red spotlight. Unfortunately, the suspect couldn’t see the red light through the cloud of dust in his rearview mirror. Choking on the dust, Berg rolled up his window and depressed the short-cycle siren button mounted on a metal plate beneath his dash. Startled by the ear-piercing blast from Berg’s siren, the suspect swerved to the right, continued for another quarter mile, and rolled to a stop.

Walking up to the car, Warden Berg could see the driver frantically moving around inside. New on the job, Berg had heard stories about the Slacks and their poaching but had not yet encountered a member of the clan in the field.

“How ya doing?” said Berg, standing a few feet behind the driver’s open window. “I see you have a fishing rod in back. Have you been fishing?” Berg couldn’t have cared less about the fishing rod. His friendly greeting was simply a way to defuse any tension resulting from the car stop.

“No,” mumbled the driver, reaching for the cigar butt in his ashtray. “Just looking around.”

“Please place your hands on the wheel where I can see them.”

The pheasant poaching suspect looked over his left shoulder at the uniformed officer. He seemed to be sizing him up and wondering why he hadn’t seen him before. The Slacks had familiarized themselves with most of the wardens in the area, keeping track of their assigned days off and learning their normal patrol habits. As has always been the case, there were dedicated wardens who worked long and unpredictable hours, and there were semiretired “good ol’ boys” an outlaw could pretty much set his clock by.

“What’s your name?” asked the suspect, placing his visibly shaking hands on the steering wheel.

“I’m Warden Berg.”

“How long have you been around here?”

“Almost a year now. Please step out of the car.”

“What’s this about?” asked the suspect, stepping from the car and quickly closing the door behind him.

“May I see some identification?”

“Can’t a man take a drive in the country without being harassed?” said the suspect, handing Berg his California Driver’s License.

Warden Berg immediately recognized the name William Ray Slack, having heard the other wardens mention it several times. “Do you still live at this Chico address, Mr. Slack?”

“Same address,” replied Slack. “Why did you stop me?”

“Where do you work?”

“I’m self-employed. Where the hell is Mercer? He can tell you who I am. I want to know why you stopped me.”

Without responding to Slack’s protests, the warden opened the suspect’s car door and reached for the gun he had spotted when Slack exited the car. . . .

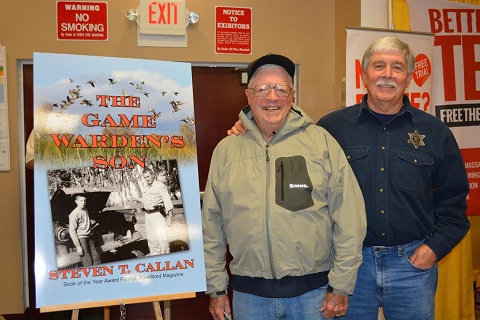

Steven T. Callan is the award-winning author of The Game Warden’s Son, named “Best Outdoor Book of 2016” by the Outdoor Writers Association of California and published by Coffeetown Press of Seattle. His debut book, Badges, Bears, and Eagles—The True-Life Adventures of a California Fish and Game Warden, was a 2013 “Book of the Year” award finalist (ForeWord Reviews).His upcoming book, Henry Glance and the Case of the Missing Game Warden, a novel, will be released in 2020. Steve is the recipient of the 2014, 2015, and 2016 “Best Outdoor Magazine Column” awards from the Outdoor Writers Association of California. He can be found online at steventcallan.com.